Stop Pearl-Clutching Over The Intel Deal

It's not socialism.

Don’t clutch pearls over a 10% Intel stake

The U.S. government taking ~10% of Intel (INTC 0.00%↑) isn’t “socialism.” It’s a strategic, minority state equity stake—a public equity injection—used as a tool of industrial policy. That’s well within America’s own tradition and common among countries that top economic-freedom rankings.

First, the facts. Washington announced a roughly 10% equity stake in Intel—an $8.9B public equity injection linked to CHIPS-era funding. Intel and major outlets detailed the deal. It does not give the government board seats or control.

History check. The “laissez-faire, unilateral free-trade” America some invoke was mostly a post-WWII interlude. For most of U.S. history, we mixed markets with tariffs, subsidies, and targeted nation-building. As Ian Fletcher put it,

America only seriously turned away from protectionism as a Cold War gambit… to prop up capitalist economies abroad and tie them to the U.S.

Corroboration. This Cold War motivation isn’t just Fletcher’s view. Robert E. Baldwin (NBER) documents that early postwar U.S. negotiators knowingly offered larger tariff concessions than they received to help allies recover and to cement an open, U.S.-led trading order—i.e., trade liberalization as a foreign-policy instrument, not a pure efficiency play. President Eisenhower’s 1955 State of the Union likewise links expanding trade with assisting friendly nations as essential to “the security of the free world.” For accuracy, note these cuts happened under reciprocal frameworks (RTAA/GATT), not literal across-the-board unilateralism—which is precisely why the asymmetric size of U.S. concessions matters.

How countries get rich: since WWII, nearly every country that sprinted from poor to rich did it with deliberate industrial policies—sometimes heavy ones.

South Korea didn’t wait around for “the market” to bless heavy industry. The state green-lit steel (POSCO), shipbuilding, and more; the HCI drive of the 1970s used directed credit, protected markets, and public R&D to build capabilities.

China has run sprawling industrial policies for decades and retained state ownership in strategic sectors while using market tools to improve them. You can debate effectiveness, but the model is not imaginary.

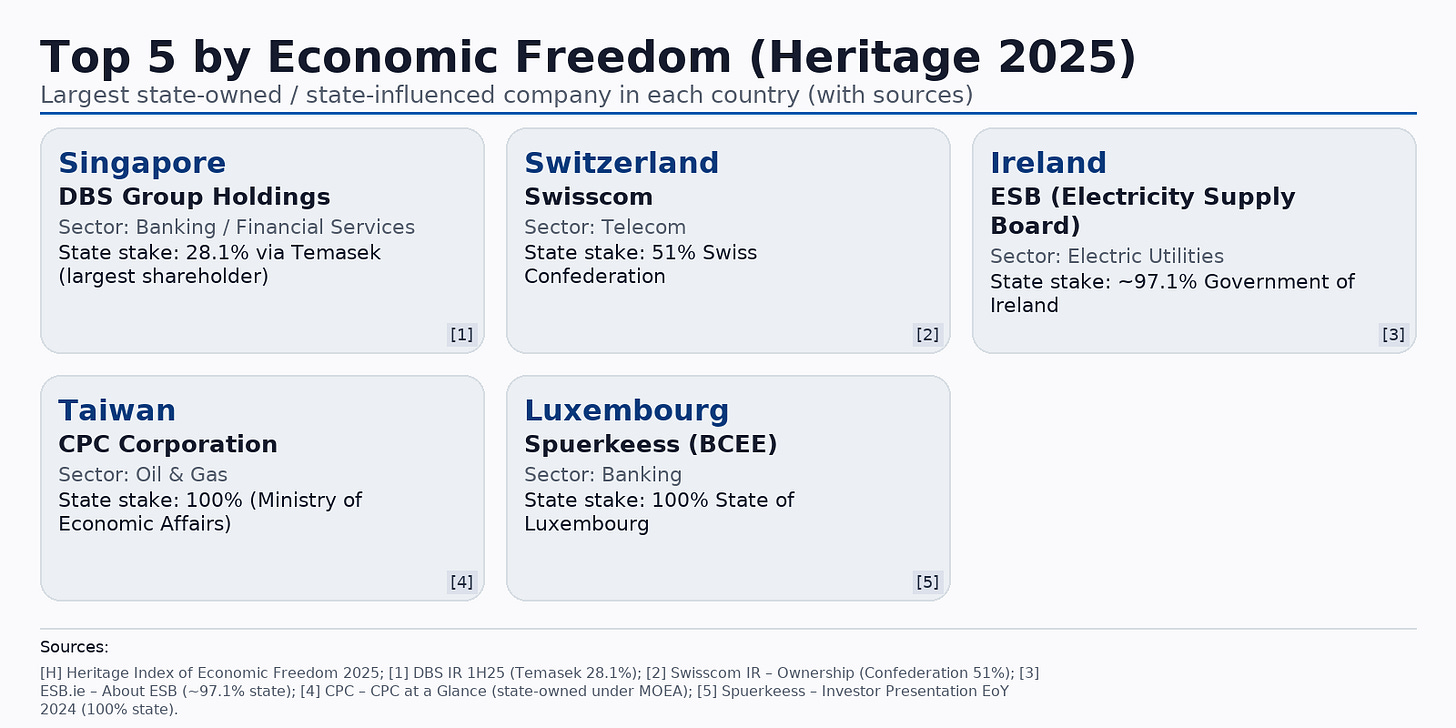

And the “freest” economies? They use the state, too. Heritage’s 2025 top five on economic freedom are Singapore, Switzerland, Ireland, Taiwan, and Luxembourg. All five have large, state-owned or state-influenced champions:

Singapore: Temasek (wholly owned by the Ministry of Finance) holds 28.24% of DBS Group, the country’s biggest bank (as of Feb. 7, 2025).

Switzerland: the Confederation owns 51% of Swisscom.

Ireland: ESB (national utility) is ~97% state-owned.

Taiwan: CPC Corporation (oil & gas) is state-owned under the Ministry of Economic Affairs.

Luxembourg: Spuerkeess (BCEE) is 100% owned by the state.

(For the rankings: 2025 top five are Singapore, Switzerland, Ireland, Taiwan, Luxembourg.)

Bottom line: even the freest economies use targeted state equity in strategic firms.

Disclosure / where I stand on the stocks. I ran a friend’s guest post at ZeroHedge last week arguing the Intel deal is bearish for Intel while noting he was bullish on Advanced Micro Devices (AMD 0.00%↑) . I’m personally agnostic on Intel’s near-term share path. Separately, AMD was Portfolio Armor’s Top Name recently, and we placed a bullish trade on it then.

None of that changes the argument here: minority, non-controlling state stakes are a mainstream tool of industrial policy used by market-oriented governments in competitive, strategic sectors.

So if a U.S. equity sliver in a strategic firm is “socialism,” then the freest economies on earth are… socialist? That’s not serious.

What’s actually changed since the early postwar era

Competition: We’re no longer alone atop the industrial heap. China is a technologically capable competitor; Europe, Japan, and Korea are advanced and aggressive. The “last man standing” moment is over.

Supply-chain reality: Chips are the new oil. Ensuring domestic capacity in leading-edge fabs is a national security problem first, a textbook market-failure second. Even critics of the Intel deal are arguing policy design, not pretending the stakes don’t exist.

The right question isn’t “government: yes or no?” It’s “how?” Guardrails matter—pricing, dilution protections, sunset/exit strategies, no political meddling. But taking a minority, non-controlling stake in a strategic manufacturer—tied to performance and capacity build-out—is a Hamiltonian move, not a Marxist one.

If you like strong defense, resilient supply chains, and high-wage industry in America, don’t clutch pearls when government uses market-oriented, equity-like tools to solve strategic problems. Save the outrage for policies that do seize control, crush competition, or turn firms into patronage machines. This isn’t that. It’s a bet that the United States should still make things that matter.