Sikh And Destroy

Harmeet Dhillon and the decline of disinterestedness.

The Decline of Disinterestedness

From “A Government of Laws” to “Who? Whom?”

In his 2013 essay The Decline of Disinterestedness, Steve Sailer recalled how, in 1991, federal agents deported a housekeeper employed illegally by the Bush family—while George H.W. Bush was still President. “John Adams, who called for ‘a government of laws, not of men,’ would have been proud,” Sailer wrote. Back then, even the president’s son wasn’t exempt from the law.

“Today”, he observed, such impartial enforcement—what older Americans once called disinterestedness—is treated as a “tiresome WASP hang-up.” Civic virtue has given way to the logic of Who? Whom?: which tribe benefits, which tribe pays.

Dhillon’s Statement and the New Hierarchy of Concern

That decline was on full display last week in a statement by Assistant Attorney General Harmeet Dhillon. Dhillon condemned California’s decision to issue commercial driver’s licenses to illegal immigrants—after two deadly crashes involving unqualified drivers—then pivoted to warn against “attacks” on Sikh and Indian-origin truckers.

“Many of these law-abiding Sikhs and Indian-origin Americans are hard-working and patriotic,” she wrote, adding that the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division “will aggressively prosecute” any discrimination against them.

It was a familiar rhetorical pattern: lead with outrage over a policy failure, close with reassurance that your own in-group deserves protection. In the age of Who? Whom?, even appeals to law and order apparently must genuflect to ethnic solidarity.

“Principle Ends Where the Tribe Begins”

Several commenters on X noticed. Mystery Grove called it “totally inappropriate that theoretical discrimination against Sikhs is given more time in this than the real-world deaths.”

Shylock Holmes noted that “the only groups willing to make a principled argument against their group self-interest are North-West Europeans.”

Fugitive Caesar was blunter: “White American employees are getting laid off by Indian managers by the hundreds of thousands… can you please do your job and investigate racial discrimination against American workers?”

And Matt Forney argued that Indian hiring networks amount to “ethnic nepotism,” displacing Americans from both trucking and tech.

Forney closed with a plea to the Assistant AG:

I ask you to put Americans first. And that means ALL Americans, including the ones who have been discriminated against by Indians or the corporations where they hold positions of power.

The Data Behind the Backlash

Those claims might sound exaggerated—until you look at the numbers.

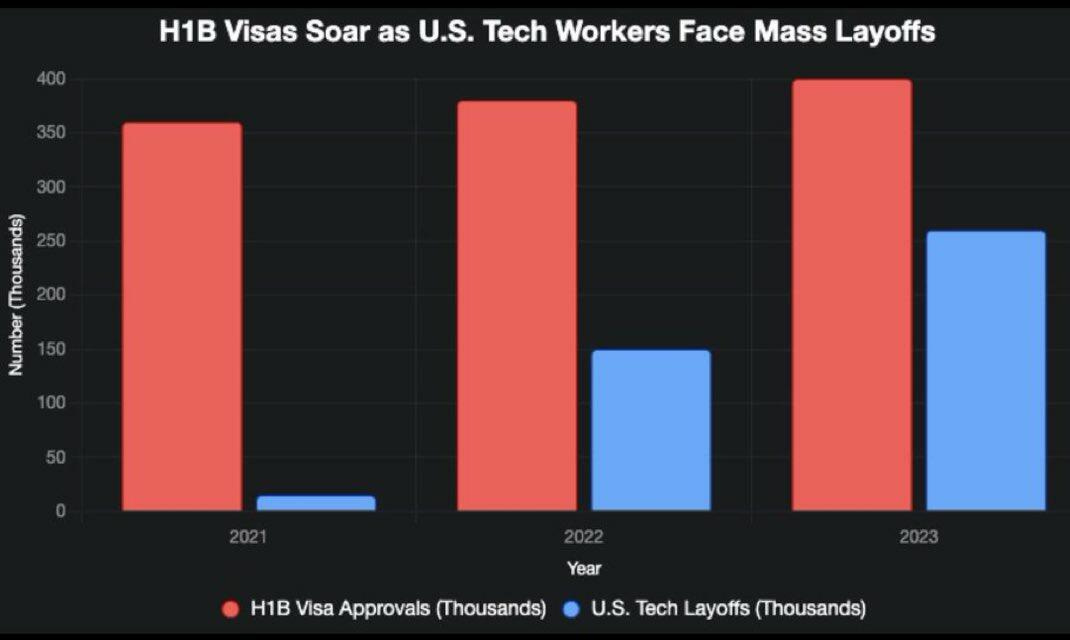

While U.S. tech layoffs have surged, H-1B approvals have continued to rise, replacing one workforce with another. The same dynamic appears in housing.

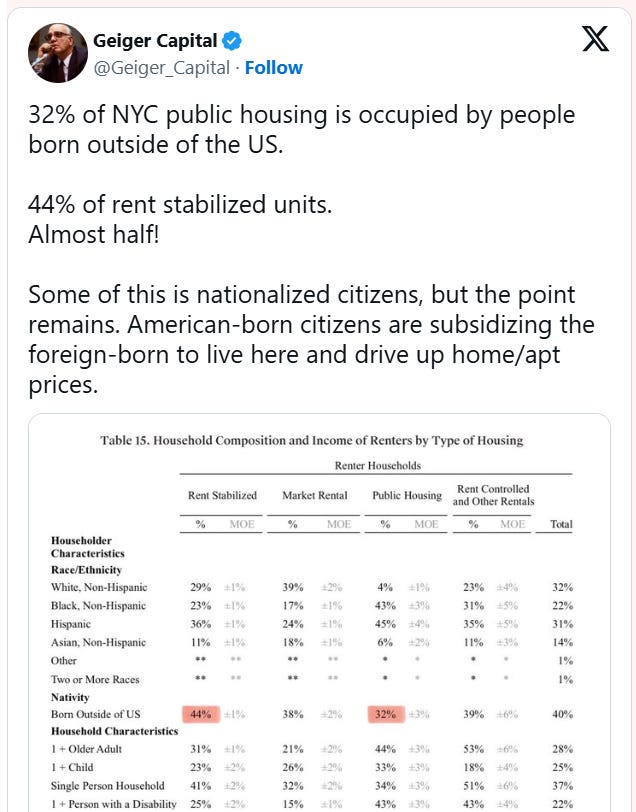

In New York, 32 percent of public-housing residents and 44 percent of rent-stabilized tenants were born outside the U.S.. As Anna Khachiyan’s thread illustrated, politicians such as Zohran Mamdani have redefined “affordability” as redistribution—away from the whiter neighborhoods and toward foreign-born constituencies.

Zohran Mamdani would accelerate current trends already moving in that direction.

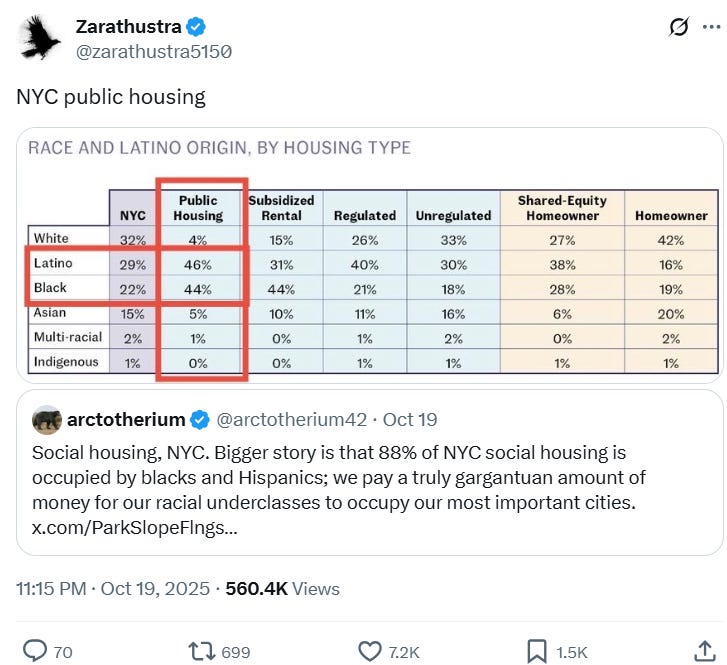

The racial (re)distribution is even more tilted.

From Disinterested Law to Patronage Politics

This is not disinterested governance; it’s a new form of patronage.

The old civic ethos—one law for everyone, regardless of family or faction—has been replaced by a patchwork of group exemptions and competing moral claims. Dhillon’s statement, well-intentioned as it was, reflected that change: every appeal to justice must now be balanced by a nod to one’s own tribe.

Sailer’s closing line from 2013 now reads as prophecy. What was once a “WASP hang-up” has become a relic of a vanished republic—a society that still believed in laws, not men.

I remember back in engineering school sometimes interacting with Mohammed, a lab assistant from Egypt (name unchanged for the sake of anonymity). For some reason, he liked to complain that American girls were racist because they wouldn’t go out with him — due, he claimed, to his large nose. What struck me most was how alien his concept of American culture was from reality.

It also reminds me of taking the bus into Oslo’s city center on a Sunday morning, years ago. I was on vacation and needed to run in for some reason I can’t recall. The bus was half full of people from the tropics and subtropics — headed, I assumed, to clean offices. It was a glum, rainy September, and everyone looked miserable and depressed. What hit me then was how unnatural it felt for people accustomed to good weather most of the year to live in a cold, sterile northern environment like Scandinavia.

The common thread in both images is disappointment.

Here’s the point: people migrate for deeply personal reasons. Beneath the resentment that figures like Mamdani feed on lies personal disappointment. And behind that disappointment are hopes, narratives, and fantasies too detached from reality to be realized.

And yet, most don’t do the obvious thing and just go home.

Instead, many use social media to project their “best life” in the West back to families, friends, and rivals. This narrative bubble keeps drawing in more migrants, who in turn pretend everything is great. The cycle continues.

Politically, I think the answer is to pop the narrative bubble. It’s fundamentally asymmetrical to the resentment and victim-driven grievances that leftists sell and agitate on.

Someone with sharp messaging like Trump might actually pull it off. DHS has shown some innovation in its marketing ads, but hope for a large-scale re-migration program is a much, much bigger project in scope.