How Hitler Made Us Lose to China

And Zohran Mamdani.

How Hitler Made Us Lose to China

And to Zohran Mamdani

Since 1945, the West has lived under a civic religion built around one dogma: Hitler was bad.

That premise is true, but the religion built on it has warped our politics, morality, and even economic policy. What began as a historical judgment became a civic theology — a permanent moral sorting system dividing the world into fascists and anti-fascists. As Eugyppius noted, it’s a “weird unacknowledged civic religion in which a cartoonish supervillain named Hitler acts as the rough equivalent of the antichrist.” When Matthew Yglesias answered that “Hitler was bad” is a pretty good basis for a civic religion, he merely said the quiet part out loud.

But antifascism itself wasn’t liberal—it was communist. It emerged from the Comintern’s Popular Front strategy in the 1930s, a vocabulary built to delegitimize the entire right, from monarchists to mere patriots. Post-1945, Western elites absorbed that moral software, stripped of Marxism’s economics but not of its logic. The result was a standing suspicion of hierarchy, nationalism, or economic planning — anything that might look “pre-fascist.” As Auron MacIntyre put it, antifascism is a poor civic creed because being *anti-*anything can’t supply a positive vision of the good.

The Vacuum Antifascism Created

Once normal right-wing politics was anathematized, a vacuum opened. On the economic side of the house, what filled it was market libertarianism: an allergy to tariffs, industrial strategy, and national preference. On the cultural side, however, liberalism increasingly used the state to advance Bioleninism: affirmative action, expansive civil-rights bureaucracies, Title VII/IX reinterpretations, the export of LGBT ideology through diplomacy and aid, DEI mandates, and more.

So the settlement wasn’t “small government”; it was small state for capital, big state for culture: a managerial order that moralized markets while engineering society. As Gray Connolly observed, conservatives and libertarians are natural adversaries with “entirely different ideas of the state, the family, basic human morality.”

The result was moralized market fundamentalism: trade without strategy, borders without meaning, prosperity without nationhood.

How That Made Us Lose To China

This moral and political allergy to national coordination left us defenseless against states that never accepted it.

Economist Brad Setser recently chronicled how China seized control of rare-earths refining, the industrial base for advanced technology. When the U.S. tried to revive its own production, China simply flooded the market, driving Western firms out.

As I noted in reply, this is where “blind worship of Milton Friedman by gilbertarians led us.” We treated protectionism as sin and dependence as virtue. Meanwhile, as Roko Mijic highlighted, China’s model today looks less like communism and more like Italian-style fascism: corporatist, nationalist, authoritarian, but not genocidal.

In other words, the very blend of state coordination and social conservatism Mussolini pioneered—the one our postwar ideology taught us to fear above all else (although Trump may be bringing a pre-war American version of it back).

How That’s Making Us Lose At Home

Recently, an American financial journalist who had spent years outside of the U.S. messaged me on X, bewildered by Trump’s consolidation of the GOP. “What happened to the Republican Party of Milton Friedman and Ronald Reagan?”, he asked. The answer is: it won. Reagan granted amnesty to millions of illegal aliens, and Friedman taught a generation to believe in borderless markets. The Reagan–Friedman synthesis became bipartisan conventional wisdom, and it destroyed any notion of conserving the actual nation.

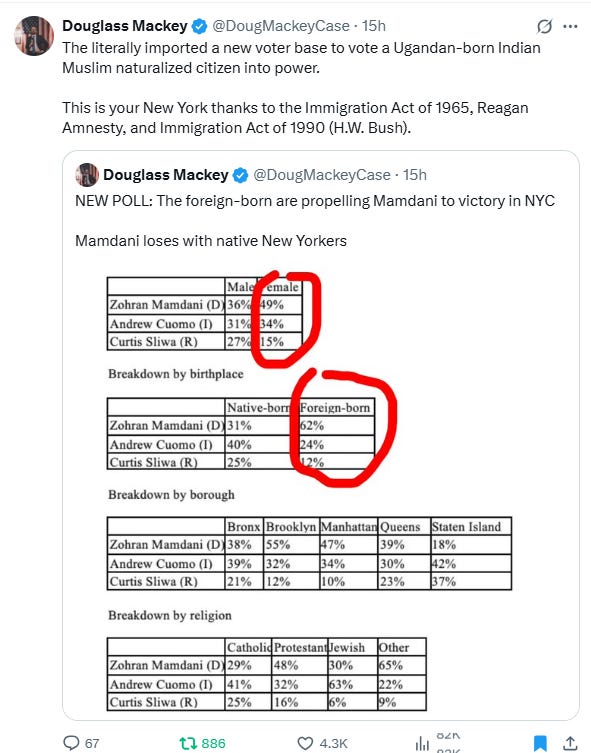

At the same time, the cultural state advanced relentlessly—the managerial apparatus that decides which identities deserve preference, which norms must be inverted, and whose speech must be policed. The postwar “antifascist” reflex coded concern for borders or demographic continuity as akin to Hitlerism. The result is visible now: as Doug Mackey noted, Zohran Mamdani—a Ugandan-born, Indian-descended socialist—leads New York’s mayoral polling, propelled by foreign-born voters.

They imported a new voter base, essentially electing a new people.

The antifascist taboo against “blood and soil” ended in demographic replacement and the erosion of any shared civic identity.

From Antifascism to Anti-Civilization

As Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry pointed out, no one disputes that “Hitler was bad.” The problem is the category error that treats anything pre-1945 and conservative as proto-Hitler — and treats Stalin, Mao, and their heirs as footnotes. By conflating fascism with Nazism and forgetting antifascism’s communist genealogy, we built a creed that despises strength and coherence while excusing rival systems that practice both.

The Hitler taboo handicapped the ability to plan, protect one’s own, guard borders, regulate immigration, and secure supply chains. In the name of defeating a ghost, we dismantled the positive virtues that sustain a civilization: prudence, solidarity, hierarchy, belonging.

Escaping 1945

Postwar elites built their legitimacy on not being fascist, and thus on never building anything that resembled the old West. But “not Hitler” is not a strategy. It’s a paralysis.

China rediscovered the uses of coordinated power. We contented ourselves with moral superiority and cheap imports. Now they hold our supply chains, and our cities elect foreign-born socialists.

If we want to survive the century, we’ll need to move beyond the ghost of Hitler and reclaim the older, deeper virtues of a civilization that knew how to build, rule, and endure.